本文主要是介绍Coursera: An Introduction to American Law 学习笔记 Week 02: Contract Law,希望对大家解决编程问题提供一定的参考价值,需要的开发者们随着小编来一起学习吧!

An Introduction to American Law

本文是 https://www.coursera.org/programs/career-training-for-nevadans-k7yhc/learn/american-law 这门课的学习笔记。

文章目录

- An Introduction to American Law

- Instructors

- Week 02: Contract Law

- Key Contract Law Terms

- Supplemental Reading

- Contract Law: Part 1

- Contract Law: Part 2

- Contract Law: Part 3

- Contract Law: Part 4

- Contract Quiz

- 法律英文

- 后记

Instructors

Anita Allen, Henry R. Silverman Professor of Law and Professor of Philosophy, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Shyam Balganesh, Professor of Law, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Stephen Morse, Ferdinand Wakeman Hubbell Professor of Law; Professor of Psychology and Law in Psychiatry; Associate Director, Center for Neuroscience & Society, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Theodore Ruger, Dean and Bernard G. Segal Professor of Law, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Tess Wilkinson-Ryan, Assistant Professor of Law and Psychology, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Tobias Barrington Wolff, Professor of Law, Penn Law, University of Pennsylvania

Week 02: Contract Law

Contract law governs how promises between two individuals are enforced. Few areas of law impact our daily lives as much as contract law, and in this module you will gain a deeper understanding of what a contract is and what makes it enforceable. Professor Wilkinson-Ryan will address what constitutes a contract, why the law enforces them, the legal meanings of words in contracts, and the important requirement of consideration. Expectation damages, or the amount a court orders someone who breached a contract to pay will also be explored, all through hypothetical and real cases.

合同法规范如何执行两个人之间的承诺。很少有法律领域能像合同法一样对我们的日常生活产生如此大的影响,在本模块中,您将深入了解什么是合同以及合同的可执行性。威尔金森-瑞安教授将阐述合同的构成要素、法律强制执行合同的原因、合同中词语的法律含义以及对价的重要要求。此外,还将通过假设和真实案例探讨预期损害赔偿,即法院命令违反合同者支付的金额。

Key Contract Law Terms

Contract

An agreement creating obligations enforceable by law. The basic elements of a contract are mutual assent, consideration, capacity, and legality. In some states, the element of consideration can be satisfied by a valid substitute. Possible remedies for breach of contract include general damages, consequential damages, reliance damages, and specific performance. See more at http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/contract

产生可依法强制执行的义务的协议。 合同的基本要素是相互同意、对价、行为能力和合法性。 在某些州,对价要素可以通过有效的替代物来满足。 对违约可能采取的补救措施包括一般损害赔偿、间接损害赔偿、信赖损害赔偿和特定履行。

Key Terms:

acceptance

Assent to the terms of an offer. Acceptance must be judged objectively, but can either be expressly stated or implied by the offeree’s conduct. To form a binding contract, acceptance should be relayed in a manner authorized, requested, or at least reasonably expected by the offeror.(http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/acceptance)

assent

An intentional approval of known facts that are offered by another for acceptance; agreement; consent. (http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/assent)

consideration

Something bargained for and received by a promisor from a promisee. Common types of consideration include real or personal property, a return promisee, some act, or a forbearance. Consideration or a valid substitute is required to have a contract. (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/consideration)

damages

A remedy in the form of monetary compensation to the harmed party (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/damages). General contract damages are damages that arise directly and inevitably from a breach of contract. In other words, those damages that would be theoretically suffered by every injured party under these circumstances.(http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/general_damages)

expectation damages

Damages awarded when a party breaches a contract that are intended to put the injured party in as good of a position as if the breaching party fully performed its contractual duties. (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/expectation_damages)

mutual assent

Agreement by both parties to a contract. Mutual assent must be proven objectively, and is often established by showing an offer and acceptance (e.g., an offer to do X in exchange for Y, followed by an acceptance of that offer). (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/mutual_assent)

offer

A promise to do or refrain from doing something in exchange for something else. An offer must be stated and delivered in a way that would lead a reasonable person to expect a binding contract to arise from its acceptance. (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/offer)

promissory estoppel

The doctrine allowing recovery on a promise made without consideration when the reliance on the promise was reasonable, and the promisee relied to his or her detriment. (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/promissory_estoppel)

statute of frauds

A statute requiring certain contracts to be in writing and signed by the parties bound by the contract. The purpose is to prevent fraud and other injury. The most common types of contracts to which the statute applies are contracts that involve the sale or transfer of land, and contracts that cannot be completed within one year. (http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/statute_of_frauds)

Supplemental Reading

Supplemental Reading

- “Contract Law: The Basics”

- “Contract Law 101”

- “Contract Law” (Encyclopedia Britannica)

- For more information, explore this website

- Excerpt from Westlaw’s Black Letter Law Outline: Contract

Contract Law: Part 1

[MUSIC] Hi, my name is Tess Wilkinson-Ryan and

I’m a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania Law School,

which was founded in 1790. I teach contract law and

law and psychology. I’m here to talk to you

about American contract law. Let’s start with what is a contract? A contract is a promissory agreement,

a set of promises, that people make to each other and

that the law recognizes and enforces. Contract law is the law of exchange, the legal rules that enforce agreements

to trade one thing for another.

I’m going to start by introducing two

foundational facts of contracting that both motivate and explain many of the

doctrines I’ll discuss in the next hour. I’ll call these facts mutual benefit and

time. First, voluntary exchanges

make people better off. Second, lots of mutually

beneficial exchanges take time. Let’s start with the idea

of mutual benefit.

Why do people engage in exchange at all? They trade because it makes

them to a person better off. Take a simple example, imagine

a world in which I have an oven but no wheat, and

my neighbor has wheat, but no oven. Now imagine we contract for

an exchange of oven time for wheat. We both like this deal, right? Because we both want to eat bread. My neighbor cannot turn inedible raw

wheat into bread without a heat source. And though I have the tool to bake with,

I can’t make bread dough without wheat. This means that the exchange

has value just by trading, we have both gotten something we

wanted and didn’t have before.

If you’re inclined to

think in terms of utility, you can think of this deal as

creating utility or value. It’s not just redistributing goods, it’s actually creating

value where there was none. This holds true for

more common market exchanges. Money for goods or services. When I agree to pay the cable company

a monthly fee for Internet services, I might complain about the exorbitant

rates and the terrible service. And I may not feel like I really profited,

but in the end, I’d rather have internet and cable

than the money that they’re charging. So I part with the money and take

the Internet in return, making both me and the cable company better off

than we were before the deal. The fact of mutual benefit, gives us some

information about the subjects of contract law, that we don’t necessarily have about

the subjects of other kinds of law. We might know that on average,

people prefer laws against theft, or that generally speaking societies

function better when there are robust civil protections

of property interests. But we don’t know that a particular

claimant really preferred to be bound by the state’s criminal code. All else being equal, or

believed himself better off in a legal system that permitted his

neighbor to sue for trespass.

In contract though, we know that each of

the parties prefers this particular legal obligation, and

we know it because they chose it. Of course, this is not to say that every

party to a contract thinks the terms could not be improved, only if that

the parties preferred this contract, the available alternatives

including no contract.

Now we come to the second foundation

of contract which seems very simple on its face and that’s time. Contracts can create mutual benefit, but unfortunately contracts

cannot create time. Time turns out though,

to be an important motivating and complicating factor in

life of an exchange. So, take for example,

my wheat for oven time exchange. Now, one way that exchange could go, is

that every time my neighbor wants to bake bread, he shows up at my house with his

bag of wheat, and his bowl of bread dough. And if my oven is free, and I’m in need of

wheat, I take the wheat and put it away, and I put his dough in the oven for him. In fact, we don’t even need a contract, much less a law of contract to make

sure that this exchange happens. We don’t need a state enforcement

mechanism making us trade. We’ll just trade because we both want to.

But now imagine for a moment that my

neighbor is not going to have any wheat for me until after the next harvest,

but need to use my oven in the meantime. He says, I promise to deliver

the wheat to you next month, if you will let me use

your oven this weekend. This is still an exchange, and it still makes us both better off,

but now I, the oven owner, am worried. If I let my neighbor use my oven now, how can I be sure he’s going to

deliver the wheat as promised later? And this is where contract comes in.

The contract is the legal mechanism

to enforce my neighbor’s promise and give me the assurances I need to

participate in this beneficial exchange. It permits me to rely on the deal. In this way, contract law facilitates

the creation of mutually beneficial deals. Voluntary exchanges create value are good,

but there are lots of reasons that exchanges require planning or

multi step performances. In order to protect the party’s

investments in their deals, contract law enforces their

promises to one another. We will see that time

makes exchanges better. The ability, for example,

to plan to plant more wheat. To know in advance whether or not I’ll have Internet service on the day

that I need to send an important email. To be able to do what I promised at a ti,

at a convenient time, rather than a time that protects me against possible

exploitation by my counter party.

But of course,

time also makes exchanges worse, because it means that things can change. The world might change, with shifts in the market making the deal

actually a losing proposition for one of the parties, or the parties’ own

preferences and goals might change. So that they’re no longer interested or

benefited in the same way. When those things happen,

the law of contracts gives people an essentially revised

cost benefit analysis to do. They have to ask themselves whether

it’s worth it to go back on the deal, in a world in which they’ll have to

compensate the other party with money. Breach of contract is really about

what happens to a deal over time? We’re typically not talking about people

who have lied about their intentions to participate in a deal, but about

people who have changed their mind for one reason or another in time.

What I’ve said about benefit and

time, these are really universal. They explain why humans have promissory

exchange mechanisms like contracts. But as you know, the title of this talk is

An Introduction to American Contract Law. So let me say a couple of things to

sort of set up what’s distinctive about the evolution and role of American

contract law at a very broad level, and then I’ll show you how this

plays out in particular doctrines. American contract law enforces

the right of autonomous agents, that’s us, to bind our future selves.

In the common law tradition, the will

of the party in question is central. Common law courts are very liberal

about letting people choose to bind themselves to whatever deals they

want, while also protecting them from contractual liability they

haven’t explicitly undertaken. The second theme of American contract

law is the notion that the role of contracts in our society

is as an economic tool. The Subject of Contract

is economic exchanges. This might seem obvious, given what

I have said about beneficial trades. But we’ll see how narrowing

the analytical framework of contract, from the promissory

obligation broadly speaking, to one of economic exchange more narrowly

has serious doctrinal implications. So we have both an underlying principle

of autonomy and freedom of contract, but with legal enforcement essentially

confined to the commercial domain. [MUSIC]

Contract Law: Part 2

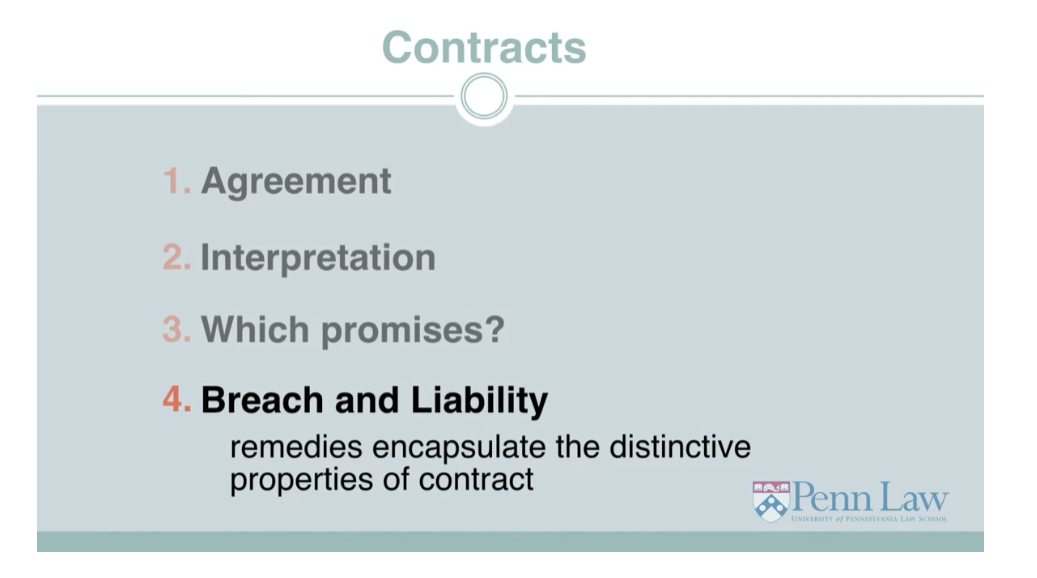

[MUSIC] From here on, I’ll structure my

talk by tracing how contract law approaches each stage in the life and

death of a deal. Which I’ll do with reference to

the examples of five seminal cases in contracts. I’ll start with how we know when we’ve got

a contract, move on to how we know what’s in the contract, identify which promises

the law cares about and which it does not, and then discuss what legal

enforcement of a contract looks like.

We start at the beginning, in the basic

case of a bi lateral contract we have two parties, each of whom

want something from the other. Who agree to a deal? In the traditional view, what was required

for contracts was a meeting of the minds. So, this is the straightforward case,

right? Joe has a leaky pipe in his kitchen,

he calls a plumber. The plumber comes out and

promises to fix it in return for a $100. Joe and the plumber look

one another in the eye and shake hands, their minds have met. At a single instant in time,

they both agreed and understood each other

to agree to the deal.

In fact, this meeting of the minds

happens even if the party’s agreements are staggered in time. So, let’s imagine, for a minute, that Joe solicits bids for his

plumbing work, via some online service. This plumber emails Joe at 9 AM, and

says, I’ll do it for $100, let me know. The plumber then waits by his computer,

ready and willing to get to work. Joe checks his email at 9:30,

sees the offer, and replies, it’s a deal. Their minds have still met there. At 9:30, the plumber was ready to go. Joe knew he was ready to go, because the plumber had made the offer and

hadn’t taken it back. So, when Joe agreed at 9:30,

there was a meeting of the minds. In fact though,

although it’s nice when it happens, meeting of the minds is not

always actually necessary.

So, now let’s make things

a bit more complicated, which we will do in the traditional way,

namely by getting everybody drunk. So in 1952 in a rural Virginia tavern,

A.H. Zehmer wrote this contract to sell his farm to an acquaintance, W.O.

Lucy, for $50,000. When Lucy tried to enforce the contract, Zehmer responded that when he wrote the

deal up, he was high as a Georgia pine, and that in fact, they were just a bunch

of two doggone drunks bluffing to see who could talk the biggest and

say the most.

Well, what now? Assume that Zimmer is telling the truth, that he was essentially just kidding the

whole time that he wrote that contract up. If that’s the case, then there is no real meeting of the minds

because when Lucy assented Zimmer did not. He was thinking to himself no contract. If we’re serious about contract as

voluntary obligations you might say, look, you can’t hold Zimmer to this

contract that he didn’t really want to be a part of. And that’s essentially what

Zimmer argued in court.

But here’s the problem. No one forced Zimmer to write and sign this contract to tell Lucy

that he was ready to sell the farm. Zimmer has voluntarily assumed the

obligations of this deal in so far as he has done the things that a person does to

indicate that they agree to something. The court says, mutual assent is of

course essential to a valid contract but the law imputes to a person

an intention corresponding to the reasonable meaning of his words and

acts. Which is to say, as long as Zimmer’s

communication, him writing and signing that deal, is reasonably interpreted

as assent then it it is assent. People are bound by the normal rules

of human discourse, promising and then saying you don’t mean it, is not

a way of getting around voluntariness.

In American contract law,

this threshold question in whether or not the parties consented to be

legally bound is determinative. If you don’t have it,

you don’t have an action in contract. You can imagine situations,

I think, where this seems unfair. The parties are negotiating for

a long time, spending lots of money on research and legal fees, trying to work

out a deal that they both seem to want, and then one party quits negotiating

altogether with no obvious reason. In many civil law jurisdictions,

we might actually see recovery of damages based on the idea that one

of the parties is at fault for the failure to contract, which means

even in pre-contractual negotiations, the parties owe each

other some kind of duty.

But not in the US,

holding aside very rare recovery and promissory estoppel,

even reasonably relying on the prospect of a deal does not create

an action in contract in the US. In American law,

the availability of remedies and contract is essentially switched on

by the manifestations of assent. If you think about it,

the way we talk about assent and contract law is actually sort of odd. Because in regular conversation, usually

we don’t talk about agreeing, full stop. Usually, we talk about

agreeing to something. In fact though, contract doctrine

essentially deals with the form and the substance separately. That is,

we ask if there’s an agreement first and then we ask what there

was an agreement to. So, there’s a question of whether or not the parties manifested intent to

be legally bound to an agreement, and then a separate set of doctrines that

are about the content of the deal. And we talk about those documents as

questions of contract interpretation.

Interpretations of big deal because it

bears on assent on breach and on damages. If we know that Jack and Jill have agreed

to a joint irrigation venture, we can’t hold Jack liable for failure to perform

until we know exactly what he agreed to.

In American contract law,

we don’t have much in the way of background principles about

what the content of a contract should be. Mostly the court is only in the business

of enforcing the will of the parties. Interpretation tells us whether or

not the parties have made a deal, whether they have breached the deal, and

what the liability for breach should be. So, I’m going to make a somewhat unusual

claim that many of the doctrines in this area are actually very easy.

Rules about, for example, when to permit outside evidence to help

interpret a contract, when a court should supply terms that are missing from a

contract, how a court should fix mistakes. The various contract doctrines that

deal with these issues boil down to the courts attempt to create

a reasonable reconstruction of what the parties actually meant to do. And if that’s not possible, then what the parties would have done,

had they thought about it. The tough cases are going to be

where the parties appear to each have had different views

of what the contract meant. That is they were agreeing

to two different deals. If a court cares about enforcing

voluntary obligations and voluntary obligations only,

this puts the court in difficult position.

So, let’s compare two cases. In case number one, we have a contract for the sale of cotton being delivered

on board the ship Peerless. Only surprise, Peerless has a peer

indeed and it’s also named Peerless. So, what does the court do? The court says, if there’s no way to

prefer one Peerless ship to the other and which ship the cotton is on matters,

then there’s actually no contract. The parties agreed to

two different things, which means that they didn’t

actually assent to a single deal. Notice here that the court

ultimately decides to under enforce. So, this is a case in which nobody is

going to get the benefit of the bargain he thought he was making.

Rather than let one party be subjected

to a contract he didn’t agree to and had to reason to think he was agreeing to,

the court chooses not to enforce at all. 300 years later, we see the same argument

come up when two parties realized that they had different things in mind

when they made their contract for the sale of chicken. The seller of chicken thought

that they just meant chicken. The buyer thought that that they

meant young chicken, fryers or boilers, rather than stewing hens. The court said, actually, if you want

to use a word in a particular way that wouldn’t be obvious to your counter party,

the onus is on you to make that clear. This isn’t like Peerless, it seems to

be true that if the court is going to hold the buyer liable for a contract he

didn’t agree to, but it says, you had reason to know, that you were agreeing to

whatever kind of chicken came your way.

One of the functions of contract law, as I said earlier, is to permit

parties to rely on the deal over time. To protect a party, who’s made herself vulnerable by

trusting that the deal will happen. We see this come up in the context

of assent and interpretation too. In order to make deals with one another, we need to be able to use a common

language and each party needs to be able to trust that the other is

using language in a normal way. And the court can then be a bit more

expansive about holding the parties liable, given that they had

clearly manifested an intent to be legally bound but botched it enough that

now the court is forced to get involved. [MUSIC]

Contract Law: Part 3

[MUSIC] So we’ve talked now about

how parties make deals and how to figure out what’s in those deals. And now we’re going to

narrow the field a bit and think about which promises are actually

the subject of contract law. The realm of voluntary obligations

is actually pretty enormous, most of us have lots of voluntarily

assumed obligations, I think, that we don’t think are legally enforceable and we

don’t think should be legally enforceable. What this means is that the set

of promissory obligations is a lot bigger than legally

enforceable contracts.

So let’s start with what’s

sort of the easiest case, and that promises that might be real. So for hundreds of years, common law

courts have refused to enforce certain kinds of informally made deals,

because they’ve been worried about fraud. The resulting doctrine is

called the statute of frauds. And what it does is it require a writing

or a written document in transfers of land and in sales of goods over

a threshold dollar amount. In these cases, what the court says to the

parties is look, if you’re serious about this deal, you have to do something to

show us your seriousness, we’re not going to enforce your agreement to sell

a house, if you didn’t get it in writing. What’s frustrating about this

doctrine to students and scholars is that it draws

a very bright line. It says, even when we have great

evidence that the parties made a real oral contract, these are cases

in which we won’t enforce for failure of a written document.

So this is a case where the rule might

actually be a pretty bad fit for it’s stated purpose, but

the purpose itself, which is weeding out contracts that weren’t

actually made is pretty uncontroversial. Okay.

So the court wants to avoid enforcing fake promises.

Next up is social promises. Almost nowhere will courts be willing

to get involved with social exchanges. Aside from more sort of

philosophical justifications, there are costs to involving

the state in private disputes. Costs to the state and also arguably

costs to sort of the social fabric. So let’s say for a minute that I’m going

to a gathering at my sister’s house and I write her a note that morning promising

that I will be over early enough to help her make dinner, this is a promise. But let me assure you that contract

law has zero interest in this promise, no matter how formally I write that note. Maybe my sister will levy

informal interpersonal sanctions? But I certainly cannot be taken to

small claims court if I wander in after the other guests have arrived, and find

a frozen pizza thawing on the counter. Whatever you might say about

my inconsiderate behavior, I surely didn’t intend to

be legally bound here. Contract law does not enforce this

kind of purely social promise.

Okay. So now we come to the most controversial

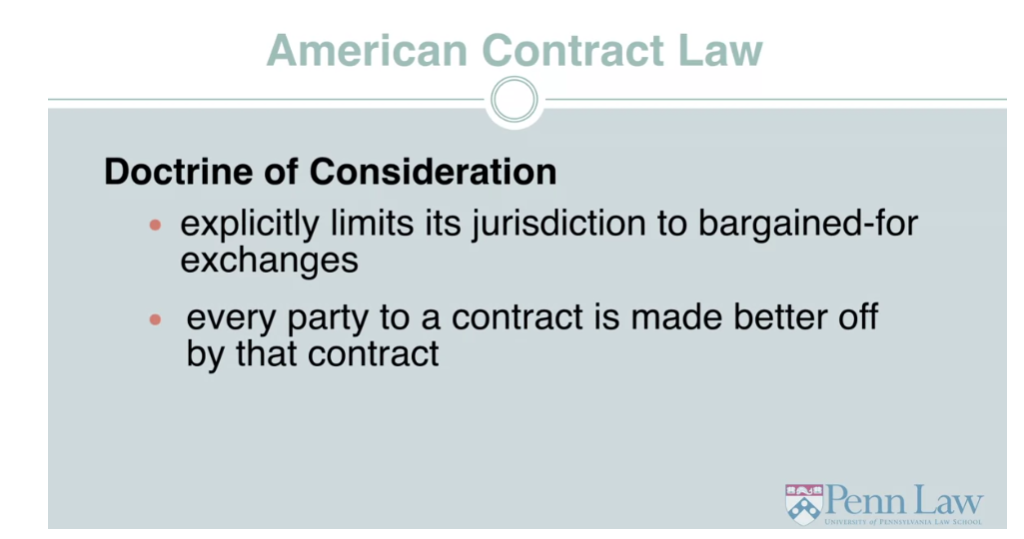

constraint on contract enforcement. American contract law explicitly

limits its jurisdiction to bargained-for exchanges, and this is

called the doctrine of consideration. One way to understand this is to think

about what I said at the start of this talk, that contract law is special, because every party to a contract is

made better off by that contract.

In a promise to give a gift, we have

a recipient whose surely better off, but a gift giver who gets nothing,

who, who is worse off. That promise to give a gift is

unenforceable under the doctrine of consideration. Of course, thinking about this

in terms of who’s better off and who is worse off,

doesn’t obviously give us the answer, because it sure seems like if I choose to

give money away it’s because there’s some measure of utility by which I’m

better off with less money. I feel better, right, there’s a warm glow. So a better way to think about

what’s going on here is that there’s a line between promises we want

people to be able to take back and those we want the law to get involved in. And one way to draw that

line is to say well, what interest does the political

system have in enforcing contracts? Is it to make people behave morally? Is it to regulate

interpersonal relationships? No. It’s essentially about commerce,

about economic relationships, and one way to identify those contracts

is by looking for true exchanges. We want to enforce deals in

which each party is in it for what they’re getting out of it. What this means that we enforce

exchanges in bargains and notably we don’t enforce gifts.

Most of the time,

it’s very easy to find consideration. If I promised to sell my car

to my neighbor for $10,000, we know that I’m giving my car because

I want what the neighbor is offering. And that my neighbor is giving up the

money, because what she wants is a car. But some times, things get messier. So let’s take the famous

1891 case of Hamer v Sidway. In this case, an uncle was worried

about his wayward adolescent nephew. Wishing to bring his nephew into line, the uncle declared that if the nephew

would abstain from drinking, smoking and gambling, until he reached age 21,

the uncle would reward him with $5000.

And lo and behold,

the nephew stopped drinking and smoking and gambling for

the next six years. Well, when the nephew brought a claim,

the court had to figure out whether this is an exchange, or

if it’s just a gift with strings attached. An exchange is enforceful, and

a gift with strings attached, is not. There’s an argument here about whether

the uncle really gets anything out of this deal, or whether the nephew

really gives anything up. After all, surely the nephew is better

off after six years of sobriety, even with out the money. But the court says no,

this is not what matters. What matters, is, literally,

the considerations. What motivated these parties? If their ascent is induced by

the promise of the other party’s performance, that’s enough. We might think that the uncle doesn’t get

much out of his nephew’s good behavior. But as long as he’s paying money in

order to get his nephew to perform, to abstain from drinking and

gambling we’re okay.

What’s troubling I think is that the

bargain for exchange in Hamer v Sidway, sure doesn’t feel like it’s

central to American economic life. On the other hand things like

promises of a bonus for work for the employee has already promised to do,

this kind of promise that sure feels like a valuable economic tool is going

to run into consideration trouble.

So take the following, a firm has employed

someone who’s near retirement age. The boss sends the employee a letter

thanking her for her years of service and promising for the first time to pay

her a bonus on retirement by way of recognition for

her contribution to the firm. No strings attached. The boss writes this letter is legal

proof of our agreement to pay you a retirement bonus, it’s signed and

let’s say even say it was even notarized. So we have ample proof that

the boss wanted this to be an legally enforceable agreement. The employee’s very happy, she stays

in her job looking forward in sort of a non-specific way to having

a slightly more luxurious retirement. So we check now on a set. Did the boss agree to this deal? Yes. Did the employee? Certainly. Can we be sure that the boss

intended it to be legally bound? Absolutely. So can she take this letter to

court to enforce the contract? No. This contract is a promise,

but it’s not an exchange. And contract law is about bargains. The doctrine of consideration

is unique to the common law. States that have modeled their own

law of contracts on principles of established common and civil law traditions have uniformly chosen

the civilian approach, declining to adopt a doctrine that’s as complicated

as it is infrequently applicable. [MUSIC]

Contract Law: Part 4

[MUSIC] Most contracts courses in US law schools,

actually begin the semester at the end of the contract, with damages for

breach of contract. Although this usually strikes

students as unnecessarily confusing, there are good reasons for it.

Namely that remedies for breach of contract, encapsulate

the distinctive properties of contract. In order to hold parties liable period, we’re going to need to know that they

assented, and what they assented to. The court is going to want

to know what the deal is, because we want to make sure we’re

holding people to the right contract. And only by knowing what the deal was,

do we know how to compensate for the deal’s failure.

So, let’s start with an example to help

illustrate one of the central rules of American contract law,

which is the rule of expectation damages. This is the case of Hawkins vs McGee.

George Hawkins, got an electrical

burn on his right hand as a child. And the result was that he had a scar,

noticeable enough to trouble him and his parents. Their family doctor, Edward McGee, noticed the scar while treating George’s

younger brother for pneumonia, and evidently got very excited, because while

in Europe during the first World War, he had seen successful skin grafts, and

thought George was a perfect test case. So, for a few years, he would periodically

offer the Hawkins’ that he could fix George’s hand, and that he could graph

skin from George’s chest, onto his hand, and create 100% perfect hand. Well, to give you a sense

of how things turned out, the case is colloquially

known as the Hairy Hand case. So, whether, because it was

a bad idea at the outset, or because the doctor couldn’t

execute the surgery skillfully, George Hawkins wound up with

a disfigured and disabled right hand. Okay, so we have a contract. George Hawkins promised to pay money, and

Dr. McGee promised him a perfect hand. Then we have a breach of contract. George Hawkins paid the money, but Dr.

McGee gave him a deformed hand. So, how do we compensate George Hawkins? Well, Dr. McGee argues that he should be

made to give George’s money back, and compensate him for any harm done. Let’s pause for a minute,

and change the hypothetical.

Let’s say for a minute, that George was

going over to Dr. McGee’s house for dinner, and the doctor accidentally

slammed George’s hand in the door, causing George significant pain and

disfigurement. Well now, Dr. McGee has to

compensate George for sure, right? With the goal being to put George

back in the position he was before the doctor injured him. Okay, so

what’s different about these cases? The contract case, and

the hand in the door case? What’s different is

the relevant counterfactual. A counterfactual is just the state of

the world that we’re comparing the current situation to. The counterfactual in

the hand in the door case, is that George’s hand doesn’t get slammed. The counterfactual in the surgery case,

is that the surgery doesn’t fail, and George gets a brand new hand. What Dr. McGee wanted, was to pay George the difference

between the hand he ended up with, something horrifying, and the hand he

had before, something uncomfortable.

But Dr. McGee voluntarily entered into

a contract, to give George a perfect hand. So, the court says, what we want to

do here, is to put George in the position he would have been in,

if the contract had been performed, which means paying him the difference

between his current horrifying hand, and a perfect hand, and

that’s going to be a much bigger number.

In contract, the remedy of expectation

damages is the default remedy. And it puts the non-breaching party, like George, in the position he would have

been in, had the contract been performed. What surprises many students of contract

though, is not necessarily that damage is measured, but the preference for

damages over specific performance. Specific performance means making

the parties do what they said they were going to do.

With the exception of real

property transfers, so land sales, American contract doctrine

severely restricts the ability of the parties to actually get

the thing they wanted from the deal. So, on the one hand, American courts are

very focused on getting the number right, making sure that the damages award

reflects exactly the amount of commitment, that the parties actually intended. But we don’t hold parties to their actual

promises, perhaps underscoring again, that what we’re doing here is

enforcing economic exchange. Where it’s reasonable to think that

the benefit can be easily expressed in dollars, rather than enforcing promises.

Indeed, in American courts, the idea that

expectation damages provide the right incentives to the parties,

has been highly influential. The notion that some breaches

are actually efficient, that they leave the breacher better off,

than he was in the contract, and the non-breaching party no worse off,

than she was under the contract. This has influenced the normative

attitude of courts, toward breach, toward a view that breaching and paying expectation damages,

is essentially a morally neutral choice. This is in keeping,

I think, with the trajectory of American contract law,

beginning with the Industrial Revolution, with the realization that

executory contracts, contracts for stuff you’re going to do later,

are economic tools, financial instruments. This insight leads me finally,

to the modern challenge, in which this financial tool increasingly mediates the

relationships between consumers and firms. So, I’d like to use my last

few words here, to flag for you, what’s perhaps the most important

modern challenge to contract doctrine. And that’s the phenomenon

of unread fine print.

In the United States, there are many contracts that are not

the object of the common law of contract. Insurance contracts

are regulated separately. Employment contracts

are part of labor law. Securities contracts

are regulated by Article nine of the Uniform Commercial Code. But other countries have

taken a different, or at least additional approach to

taxonomizing contracts, based not so much on what the contract is,

so much as who the parties are. Other countries have included form

contracts as a separately regulated area of contract. So, let’s just step back a minute.

In a general matter, we can think about contracts as

belonging to three categories. The first is contracts

between individuals. The deal that I make with someone who’s

selling a used car on Craigslist. The agreement between Dr.

McGee and George Hawkins. The sale of a house from one

homeowner to another, or an uncle’s promise to pay his

nephew not to be a wastrel. These deals are sort of the easiest

ones to fit into a contract paradigm, because we have actual people who

negotiate and draft an agreement. And since these are humans with cognition,

we know what it means, when we talk about their motivations and

their intentions. The problem,

is that these are the deals for which contract doctrine is

arguably the least relevant. Because these are the deals least

likely to be resolved by courts, for lots of reasons. First, these deals are just

few on the ground. Unless you’re Warren Buffet, I just don’t

think you’re drafting that many contracts. The financial stakes in these contracts

are quite low typically, meaning that the costs of bringing an action is often

going to swamp the expected value of litigation. And in the meantime, the social and psychological stakes of deals between

individuals, can often be quite high, so that parties often prefer to figure things

out informally in a way that’s the least destructive to their relationships,

to their standings in the community.

Some scholars would argue that American

contract law, really isn’t made for these cases anyhow. What it’s really about

is commercial deals. And indeed, this should resonate with

my description of development of modern contract law, in the context

of the Industrial Revolution. When we have two commercial actors,

whether its a farmer and a bodega, or Apple and Google making a deal, we have

a nice robust role for contract doctrine. Because we’re going to be talking about

parties who are represented by counsel, meaning that they,

they’re going to know what the rules are. I’m talking about deals

that are big enough, that the prospect of legal enforcement has

real effects on how the parties draft and then perform their deals. Gets a little bit trickier, to talk about

things like a meeting of the minds, when the actors are entities

rather than humans. But there are always humans involved,

of course. So, it’s just a matter of locating the relevant humans. And also we can rely on doctrines like

objective assent, to make clear and easier, how we understand what

it means to, for example, agree. So, now for the third category of

contract, the category that most of us have the most experience with, and that’s

contracts between individuals and firms. In other words, the form contracts that

you have with AT&T and Comcast, and iTunes, Facebook, Vanguard,

Chase, and Visa, et cetera. These are take it or leave it deals,

between consumers and companies. And by a simple head count,

these account for the vast majority of contracts

active at any given moment.

But these contracts pose real

challenges for contract doctrine, and the consequences of how we deal with these

challenges are increasingly serious, as consumer contracts are increasingly

central to how individuals participate in American economic life. The normal ways that we talk about

negotiation and promise, and assent, they fit only uneasily,

in a form contracts context, where everyone acknowledges that only

the drafting party, only the company, knows what’s in the terms,

because most consumers don’t read them. Other jurisdictions, including civil

law countries as well as the UK, have taken legislative action to

constrain the content of form contracts. But American courts, and

legislatures tend to view substantive restrictions on contract

terms as sort of overly paternalistic. Preferring to let the market weed

out unfavorable or unfair terms. As we watch this area unfold over time,

we’ll see, both how the norms and patterns of everyday commercial interactions

push contract law to adapt, but also how increasing contractualization, affects the

American economic and social discourse. [MUSIC]

Contract Quiz

B. The modern doctrine of assent is about what the parties manifested to one another, not their secret intentions. In this case, Jane assented when she verbally agreed and shook Caleb’s hands, because those are actions reasonably interpreted by Caleb as Jane’s agreement to the deal.

D. In contracts, the usual rule is that the non-breaching party gets money damages in an amount sufficient to put him the position he would have been in had the contract been fulfilled. In this case, if the contract were fulfilled, the homeowner would have no mess and a fixed pipe, so the plumber has to pay him not only the cost of cleaning up the mess but also of actually fixing the pipe as promised. 在合同中,通常的规则是,非违约方获得金钱损害赔偿,赔偿金额应足以使其处于履行合同情况下应有的地位。

法律英文

obligations :义务

doctrine:美 [ˈdɑːktrɪn] 教义,官方声明

breach of contract:违约

promissory:美 [ˈprɑməˌsɔri] 约定的;承诺的

A contract is a promissory agreement, a set of promises, that people make to each other and that the law recognizes and enforces. 合同是一种约定的协议,是人们相互做出的一系列承诺,是法律认可和强制执行的。

voluntary:美 [ˈvɑːlənteri] 自愿的

voluntary exchanges make people better off 自愿交换使人们过得更好

exorbitant:美 [ɪɡˈzɔːrbɪtənt] 过高的

oven:美 [ˈʌvn] 烤箱

dough:美 [doʊ] 生面团

bind:法律约束

American contract law enforces the right of autonomous agents to bind our future selves. 美国合同法强制执行自主代理人约束我们未来自我的权利。

enforcement:执行,实施

confine:美 [kənˈfaɪn] 限制,局限

So we have both an underlying principle of autonomy and freedom of contract, but with legal enforcement essentially confined to the commercial domain. 因此,我们既有合同自主和自由的基本原则,但法律执行基本上仅限于商业领域。

plumber: 美 [ˈplʌmər] 水管工

Joe has a leaky pipe in his kitchen, he calls a plumber. 乔的厨房水管漏水,他打电话给水管工。

tavern:美 [ˈtævərn] 酒馆,客栈

acquaintance:美 [əˈkweɪntəns] 认识的人,熟人,泛泛之交

assent:美 [əˈsent] 赞成,同意

jurisdiction:美 [ˌdʒʊrɪsˈdɪkʃn] 司法权;裁判权;司法;权限;

estoppel:美 [əˈstɑpəl] 禁止反悔,禁止翻供

promissory estoppel:美 [ˈprɑməˌsɔri əˈstɑpəl] “promissory estoppel”是一种法律原则,通常用于合同法领域。它指的是当一方做出了明确的承诺,导致另一方在行为或决策上产生了合理的依赖,从而使得原承诺方不能反悔或撤销承诺的情况。在这种情况下,法律可能会阻止原承诺方否认承诺或采取反对依赖方利益的行动。 promissory estoppel通常用于解决当事人之间没有正式合同但有明确承诺的情况,以确保公平和正义。

remedy:美 [ˈremədi] 补救,法定补偿

manifestations:美 [ˌmænəfeˈsteɪʃənz] 表现,显现

In American law, the availability of remedies and contract is essentially switched on by the manifestations of assent. 在美国法律中,补救措施和合同的有效性基本上取决于同意的表现。

So, there’s a question of whether or not the parties manifested intent to be legally bound to an agreement, and then a separate set of doctrines that are about the content of the deal. 因此,有一个问题是,双方是否表明了受协议法律约束的意图,然后是关于交易内容的一套单独的理论。

cotton:美 [ˈkɑːtn] 棉花

legally enforceable contracts: 可依法执行的合同

statute of frauds: 反欺诈法;防止欺诈法

wayward:美 [ˈweɪwərd] 任性的

an uncle was worried about his wayward adolescent nephew. 一个叔叔很担心他任性的青春期侄子。

abstain:美 [əbˈsteɪn] 克制,戒除,放弃

abstain from drinking, smoking and gambling

a gift with strings attached:"a gift with strings attached"是一个英语习语,意思是赠送礼物时附带了一些条件或限制。这表示接受礼物的人在享受礼物时必须满足某些要求或遵守特定的规定。这种情况下,接受礼物可能并不完全是无条件的,而是附带了一些约束或限制。

consideration:对价。在合同法中,“对价”指的是承诺人从受让人那里获得的并且是通过讨价还价得到的东西。对价可以采取各种形式,包括实物或个人财产、回报承诺、某种行为或者是不采取行动(忍让)。简而言之,对价就是每一方为对方的承诺所给予或同意给予的东西。在合同法中,对价或者有效的替代品是确立具有法律约束力的合同所必需的。这确保了双方都提供了具有价值的东西,从而使得合同具有约束力。

colloquially:美 [kə’loʊkwɪrlɪ] 用白话地;用通俗语地;口语地

default:不履行,违约

non-breaching party:非违约方

the remedy of expectation damages is the default remedy. And it puts the non-breaching party, like George, in the position he would have been in, had the contract been performed. 预期损害赔偿的救济是违约救济。这将像乔治一样的非违约方置于合同履行时他本应处于的地位。

specific performance:特定履行;强制履行

在法律领域,specific performance指的是法院对合同中某一方当事人作出的具体执行裁定。这意味着法院要求违约方履行其合同义务,而不是通过支付赔偿金或损失赔偿来解决违约。通常情况下,specific performance适用于合同中涉及独特或独一无二的物品或服务的情况,因为赔偿金无法完全弥补损失。例如,如果某人违约未按合同约定出售房产,法院可能会裁定要求该人执行合同,即出售房产。specific performance通常被视为一种有力的法律手段,以确保合同当事人履行其承诺。

damages award: 损害赔偿金

American courts are very focused on getting the number right, making sure that the damages award reflects exactly the amount of commitment, that the parties actually intended 美国法院非常注重获得正确的数字,确保损害赔偿裁决准确反映当事人实际意图的承诺金额

financial instruments:金融商品;金融工具;金融手段

economic tools, financial instruments 经济工具、金融工具

taxonomy:美 [tækˈsɑnəmi] 分类学,分类 注意发音

stake:美 [steɪk] “stake” 的中文意思是 “赌注”、“利害关系” 或 “股份”。

litigation:美 [ˌlɪtɪˈɡeɪʃn] 诉讼;起诉;打官司

swamp:美 [swɑːmp] 淹没,压倒

The financial stakes in these contracts are quite low typically, meaning that the costs of bringing an action is often going to swamp the expected value of litigation:这些合同的财务利益通常相当低,这意味着提起诉讼的成本往往会超过诉讼的预期价值。

后记

2024年4月24日15点59分开始学习第二周的课程:American Contract Law。2024年4月25日15点41分完成第二周的学习。两天大概花费时间为2h。

这篇关于Coursera: An Introduction to American Law 学习笔记 Week 02: Contract Law的文章就介绍到这儿,希望我们推荐的文章对编程师们有所帮助!