本文主要是介绍美团饿了么偷听门_为什么我们认为我们的电话正在偷听我们的声音,希望对大家解决编程问题提供一定的参考价值,需要的开发者们随着小编来一起学习吧!

美团饿了么偷听门

重点 (Top highlight)

Months ago, before lock-down started, I had a friend round for dinner. He was on the keto diet; a high-fat, low-carb regime, mainly consisting of meat and cheese. Also fine, he told me, are Shirataki Noodles. I didn’t know what to cook. Shirataki Noodles were not a helpful suggestion.

分钟前开始onths,锁定下来开始前,我有一个朋友来吃饭。 他在吃酮饮食。 一种高脂肪,低碳水化合物的食品,主要由肉和奶酪组成。 他告诉我,白rat面也不错。 我不知道会做饭 白rat面不是一个有帮助的建议。

Another guest was a vegan, so meat, fish, eggs, and cheese were out. I found myself mumbling dark comments about the keto diet. In the end, we went out to a restaurant.

另一个客人是素食主义者,所以肉,鱼,蛋和奶酪都掉了。 我发现自己在抱怨关于酮饮食的黑暗评论。 最后,我们去了一家餐厅。

Later that evening, as I scrolled through Twitter an ad popped up for the keto diet. I’d never shown the remotest interest in dieting before, and my mind raced. Were Facebook and Twitter secretly listening to my conversations? I pictured Zuckerberg with a headphone-clad, Gene Hackman-like figure in the shadows, identifying ads to push to me.

那天晚上晚些时候,当我在Twitter上滚动浏览时,弹出了一个关于酮饮食的广告。 以前我从未对节食表现出最浓厚的兴趣,所以我的心思跳动了。 Facebook和Twitter是否在偷听我的对话? 我用阴影里戴着耳机,基因·哈克曼(Gene Hackman)的身影给扎克伯格拍照,找出了要推向我的广告。

手机有耳朵,手提电脑有眼睛 (Phones have ears and laptops have eyes)

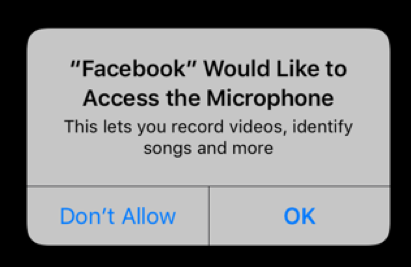

So, to come straight out with it: No. Our phones are not secretly listening to us. There are lots of ways we know Twitter and Facebook can’t do this. When a developer writes an app for iOS it runs on the Apple-controlled operating system. Facebook can’t just access the microphone and start recording. The app has to go through code written by Apple. When Facebook requests audio, Apple asks the user whether they want “Facebook” accessing the microphone. If they do, it sends an audio stream to Facebook. If they don’t, it doesn’t. Apple’s code is a software bouncer: If an app doesn’t have an invitation from the user, it ain’t getting in.

因此,直接说出来:不。我们的电话不是在偷听我们。 我们知道有很多方法,Twitter和Facebook无法做到这一点。 当开发人员为iOS编写应用程序时,它将在Apple控制的操作系统上运行。 Facebook不能只是访问麦克风并开始录音。 该应用程序必须经过Apple编写的代码。 当Facebook请求音频时,Apple询问用户是否要“ Facebook”访问麦克风。 如果他们这样做,它将向Facebook发送音频流。 如果他们不这样做,那就不会。 苹果的代码是一个软件弹跳器:如果一个应用没有用户的邀请,它就不会进入。

When an app uses the microphone, a bar appears at the top of the screen. There was no bar at the top of my screen when I was moaning about my keto friend. But still, I feel disconcerted. I go through my phone and review which apps have access to my microphone. I do this, knowing it is not necessary. But also I think it is best to check just in case. I’m reminded of the myth that at Harvard it is good luck to rub the shoe of a particular statue. Ivy League students are too smart to be superstitious. But still, the left shoe is shiny from being rubbed. You know, just in case.

当应用程序使用麦克风时,屏幕顶部会出现一个栏。 当我抱怨我的酮类朋友时,屏幕顶部没有任何栏。 但是,我还是感到不安。 我通过手机检查了哪些应用程序可以访问我的麦克风。 我这样做是因为知道没有必要。 但我也认为最好以防万一。 我想起了一个神话,那就是在哈佛,磨擦特定雕像的鞋子是好运。 常春藤盟校的学生太聪明了,不能迷信。 但是,左鞋被擦擦后仍会发亮。 你知道,以防万一。

Maybe, I think, Facebook found a way to bypass Apple’s security. But again, we can check this by monitoring the data Facebook is sending from our phones. If Facebook was sending audio, we’d see it. Even if they found a way to disguise the traffic, sending this audio would require a massive amount of bandwidth. You’d know about it when your phone bill turned up. What’s more, if we run the numbers, we see it isn’t feasible. “Voice-over-internet call takes something like 24kbps,” Antonio García Martínez says in Wired, “that’s about 20 petabytes per day, just in the U.S.” Facebook’s data centers are big, but not that big.

我认为,也许Facebook找到了一种绕过苹果安全性的方法。 但是同样,我们可以通过监视Facebook从我们的手机发送的数据来检查这一点。 如果Facebook正在发送音频,我们会看到。 即使他们找到了掩盖流量的方法,发送此音频也将需要大量带宽。 当您的电话账单出现时,您会知道的。 而且,如果我们进行数字运算,我们会发现这是不可行的。 AntonioGarcíaMartínez在《 连线 》中说: “通过互联网进行语音通话大约需要24kbps,每天在美国大约需要20 PB。” Facebook的数据中心很大,但并不那么大。

On top of this, there is the cost and computational complexity of processing the audio, finding keywords, and serving ads. And the question of whether it would actually work. As Martínez says, “Human language is overrun with sarcasm, innuendo, double-entendre, and pure obfuscation.” Siri barely works when I speak directly to it. Computers aren’t yet smart enough to make sense of our speech. Facebook simply can’t be recording our audio all the time. Your phone would get hot, the battery would run down. Forget data protection laws, the laws of physics protect us here.

除此之外,还存在处理音频,查找关键字和投放广告的成本和计算复杂性。 以及它是否会真正起作用的问题。 正如马丁内斯(Martínez)所说,“人类的语言被嘲讽,影射,双重意图和纯粹的迷惑所淹没。” 当我直接与Siri交谈时,Siri几乎无法工作。 电脑还不够智能,无法理解我们的讲话。 Facebook根本无法一直录制我们的音频。 您的手机会变热,电池会耗尽。 忘记数据保护法则,物理法则在这里保护我们。

Facebook denies secretly recording audio, too. Although I find that the least compelling piece of evidence.

Facebook也否认秘密录制音频 。 尽管我找到了最不引人注目的证据。

有人要披萨吗? (Anyone for pizza?)

I write software. I have friends who work at Facebook. I do things with APIs and mobile apps, so I’m in as good a position as I can be to judge the veracity of these claims, and yet I still can’t shake the suspicion that they’re listening. Could they have somehow found a way around physics? It has become my “9/11 was an inside job.” Listengate.

我写软件。 我有在Facebook工作的朋友。 我使用API和移动应用程序处理事务,因此我可以尽力判断这些声明的准确性,但是我仍然不能怀疑他们在听什么。 他们能以某种方式找到绕过物理学的方法吗? 这已经成为我的“ 9/11是一项内部工作”。 侦听门。

Twice now I’ve found myself doing little tests. “Man, I’d sure love a holiday in the Bahamas,” I say out loud to no one, my phone resting on the side with the Facebook app open. “Gosh, my car insurance is expensive. Would be real great if someone could find a cheaper quote.” Nothing. I feel silly. But still, the next day, I look at each ad with renewed suspicion. Journalists, smart journalists who debunk conspiracies, are lured into these too. New Statesman ran a similar (and equally unscientific) study to mine. Of course, they got similar results: Facebook isn’t listening.

现在我发现自己做了两次小测试。 “老兄,我一定会喜欢在巴哈马度假,”我对所有人都大声说,我的手机放在Facebook应用打开的旁边。 “天哪,我的汽车保险很贵。 如果有人能找到更便宜的报价,那将是非常不错的。 “ 没有。 我觉得很傻。 但是,第二天,我又再次怀疑每个广告。 揭穿阴谋的记者,精明的记者也被吸引到其中。 新政治家对我 进行了类似 (但同样不科学)的研究。 当然,他们得到了类似的结果:Facebook没有在听。

This isn’t the only rumor that I find reasonable people repeating. Planned obsolescence: the idea that old products stop working just as new ones come out. Software updates are designed to slow older devices. Smartphones cause cancer. Hackers are secretly watching you through your laptop camera. That sort of thing.

这不是我发现有理性的人在重复的唯一谣言。 计划中的过时:旧产品就像新产品一样停止工作的想法。 软件更新旨在减慢旧设备的速度。 智能手机会致癌。 黑客正在通过笔记本电脑相机秘密监视着您。 诸如此类的事情。

有时候只是数学 (Sometimes it’s just maths)

The problem is, technology companies do shifty things. Listening to us through our microphones to sell ads is exactly the sort of thing they would do. It’s very much in character. Apple was slowing the processors of old phones — admittedly to gracefully handle degraded batteries, but we were right to think our phones were getting slower. And there are more nefarious examples. “Apps were automatically taking screenshots of themselves and sending them to third parties,” sad Christo Wilson, a PhD student at Northeastern University, after examining multiple Android apps. Facebook has a history of hiring “outside contractors to transcribe clips of audio from users of its services” and storing messages that “users wrote out but did not post.” There are loads of examples of these. Our privacy has been violated before.

问题是,科技公司做些杂事。 他们会通过麦克风听我们的声音来出售广告。 非常有特色。 苹果正在减慢旧手机的处理器速度 -当然可以优雅地处理退化的电池,但是我们认为我们的手机越来越慢是正确的 。 还有更多邪恶的例子。 东北大学的博士生克里斯托·威尔逊(Christo Wilson)在研究了多个Android应用程序后,“悲伤地将应用程序的截图自动发送给第三方”。 Facebook 的历史悠久 :“聘请外部承包商从其服务用户那里抄录音频片段”,并存储“ 用户已写但未发布 ”的消息。 有很多这样的例子。 之前我们的隐私已受到侵犯。

What’s more, sometimes advertising coincidences are uncanny. There’s my keto example, but everyone has their own story. When PJ Vogt asked for examples on the podcast Reply All, he received dozens of replies. It’s “spooky,” people said time and time again. They said something and the next day it popped up in a feed somewhere.

而且,有时广告巧合是不可思议的。 我有个keto例子,但是每个人都有自己的故事。 当PJ Vogt在播客“ 全部答复”中 询问示例时,他收到了数十份答复。 人们一次又一次地说,这是“诡异的”。 他们说了些什么,第二天,它突然出现在某个提要中。

The explanation, professor David Hand, PhD, explained to the BBC, is just maths. “If you take something that has a tiny chance of occurring and give it enough opportunities to occur, it inevitably will happen.” The odds of showing someone a product they were just talking about is something outrageous. One in a million, say; the phrase we use when we mean something is basically impossible. With those odds, every time Facebook shows an ad, 2,500 people will have just been talking about it. If you were thinking about something common, like pasta, and later saw an ad for it, you might not think anything of it. But when it’s something obscure it sticks out. This is the Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon: coined by someone named Terry Mullen, after reading about an obscure political faction, the Baader-Meinhof group, and then coming across them again in an unrelated article.

大卫·汉德(David Hand)博士向英国广播公司(BBC)解释的解释只是数学。 “如果您采取的可能性很小,并且有足够的机会发生,那么这种情况将不可避免地发生。” 向某人展示他们刚刚谈论的产品的可能性实在令人发指。 例如,百万分之一; 当我们指的是某种东西时,我们使用的短语基本上是不可能的。 有了这些机会,Facebook每次显示广告时,就会有2500人在谈论它。 如果您想着一些常见的东西(例如面食),后来又看到了广告,那么您可能会一无所获。 但是,当它变得晦涩时,它就会伸出来。 这就是Baader-Meinhof现象:由特里·穆伦(Terry Mullen)创造,是在阅读了一个晦涩难懂的政治派别-Baader-Meinhof小组后 ,在不相关的文章中再次遇到的。

We’ve been duped. Tricked by our illogical gray matter. Humans are pattern-spotting machines. We’re so great at it, we spot patterns even when none exist.

我们被骗了。 被我们不合逻辑的灰质所欺骗。 人类是点样机。 我们非常擅长,即使没有模式,我们也会发现模式。

与魔法无异 (Indistinguishable from magic)

I don’t find these explanations particularly satisfying, though. These uncanny events happen too often to be chance. What I really want to see is the series of decisions that lead to me being shown that particular ad at that particular time; to explain how the algorithms synchronized with my lived experience. Because these ads aren’t chance coincidences. They are the result of a recommendation engine using data points it has on me.

不过,我认为这些解释并不特别令人满意。 这些不可思议的事件经常发生,没有机会。 我真的想看到的是,被证明导致了我一系列决策在特定时间特定的广告; 解释算法如何与我的生活经验同步。 因为这些广告不是偶然的巧合。 它们是推荐引擎使用它对我的数据点的结果。

Why don’t Facebook and Google listen to us? They don’t need to. They know our age, our location, our interests, the sites we’ve visited, things we’ve looked at. Twitter didn’t advertise the keto diet to me because it overheard me talking about it. It did so because, without thinking, I Googled what to cook for my ketosis-induced friend and one of the sites I visited had a tracking pixel on it, which captured this nugget of information to advertise back to me. Our digital lives are so intertwined with our “real” lives that it’s easy to forget what you Googled and what you just thought. Google doesn’t need to read our minds; we type into it what we’re thinking. Facebook is not listening to our words. It’s listening to our thoughts.

为什么Facebook和Google不听我们的话? 他们不需要。 他们知道我们的年龄,我们的位置,我们的兴趣,我们访问过的站点以及我们所关注的事物。 Twitter并没有向我宣传酮饮食,因为它无意中听到了我的谈论。 这样做是因为,我没有想过,就用Google搜索了由酮症诱发的朋友要做什么,而我访问过的一个网站上面有一个跟踪像素,该像素捕获了这些信息,然后向我做广告。 我们的数字生活与我们的“真实”生活交织在一起,很容易忘记您谷歌搜索的内容和您的想法。 Google不需要阅读我们的想法; 我们在其中输入我们的想法。 Facebook没有听我们的话。 在听我们的想法。

“Any sufficiently advanced technology,” Arthur C. Clarke famously said, “is indistinguishable from magic.” And technology has become sufficiently advanced. Even 10 years ago, Facebook was gathering 500TB of data a day. With that much data, it can make connections that seem magical.

“任何足够先进的技术,”亚瑟·克拉克(Arthur C. Clarke)著名地说道,“与魔术没有区别。” 技术已经变得足够先进。 即使在10年前,Facebook 每天仍在收集500TB的数据 。 有了这么多数据,它可以使连接看起来很神奇。

这是Facebook的世界,我们生活在其中 (It’s Facebook’s world, we just live in it)

These explanations are no more satisfying than finding out how magicians do their tricks. Mirrors, magnets, and trap doors are so prosaic it feels hard to believe they are behind what we saw on stage. We’ve all played with cards, so we think we know what is possible. We forget that magicians have practiced manipulating cards for thousands of hours. A pack of cards in their hands is not the same as it is in ours. Similarly, technology companies operate in a way that is fundamentally different from the way we do. We hear they are breaching privacy laws, but often in subtle ways. Can anyone really explain which particular privacy violations Facebook’s record-breaking $5 billion fine covers? (And, indeed, what all the fines since then have been for as well.)

这些解释仅比找出魔术师的技巧如何就令人满意。 镜子,磁铁和活板门太平淡了,很难相信它们落后于我们在舞台上看到的东西。 我们都玩过纸牌,所以我们认为我们知道有什么可能。 我们忘记了魔术师已经练习了数千个小时的卡片操作。 他们手中的一包纸牌与我们手中的一包纸不同。 同样,技术公司的运营方式与我们的运营方式根本不同。 我们听说他们正在违反隐私法,但通常以微妙的方式。 谁能真正解释Facebook违反记录的50亿美元罚款记录中哪些具体侵犯隐私行为? (实际上,从那以后,所有罚款都还包括在内。)

This low-trust environment is the perfect breeding ground for conspiracy theories. “Research shows,” says Professor Karen Douglas, PhD, of the University of Kent, “that people are drawn to conspiracy theories when they feel powerless.” And compared to Facebook we are powerless. The idea that we have found something out allows us to regain some of our power: We know their secrets. “People who believe in conspiracy theories can feel ‘special,’” psychologist Anthony Lantian, PhD, writes, “they may feel that they are more informed than others.”

这种低信任度的环境是阴谋理论的理想滋生地。 肯特大学的Karen Douglas教授说: “研究表明,人们在感到无能为力时就会被阴谋论所吸引。” 与Facebook相比,我们无能为力。 我们发现了一些问题的想法使我们可以重新获得一些力量:我们知道他们的秘密。 心理学家安东尼·兰蒂安(Anthony Lantian)博士写道 :“相信阴谋论的人会感到'特殊',他们可能会觉得自己比其他人更了解情况。”

In Democracy and Truth, Sophia Rosenfeld suggests conspiracy theories thrive in societies with large gaps between the governing and the governed. Technology companies may not govern us (not literally, not yet), but they have access to knowledge and resources we don’t. There is a growing gap between the things they can do and our understanding of how they do them. In The Workshop and the World, Robert Crease talks about how this “creates a rift between those unable to understand this special language and those who do, making it easy for the former to distrust the latter.”

在民主和真理,索菲亚·罗森菲尔德提出的阴谋论在社会的繁荣与大间隙之间的管理和荷兰国际集团的管理编辑 。 科技公司可能不会(不是字面上,不是现在)统治我们,但它们可以获取我们所没有的知识和资源。 他们可以做的事情与我们对他们如何做的理解之间的差距越来越大。 罗伯特·克雷斯(Robert Crease)在《讲习班与世界 》中谈到了“如何在无法理解这种特殊语言的人与能理解这种特殊语言的人之间造成裂痕,从而使前者容易不信任后者。”

We often think conspiracy theories belong to the paranoid. But a kinder explanation is that these ideas come from powerlessness. Even software developers, Jeff Atwood writes, “serve at the pleasure of the king.” Each is at the mercy of a bigger company, higher up the food chain. In comparison to tech giants with millions of users we are but specks, tiny and powerless: digital peasants. How much nicer to feel special: someone is listening to me. I count, I matter! Even if just to sell me a faddy low-carb diet. Not that I want Facebook to listen in on me, but it’s almost more depressing that we’re not even important enough for them to want to try.

我们经常认为阴谋论属于偏执狂。 但是,更合理的解释是这些想法来自无能为力。 杰夫·阿特伍德(Jeff Atwood)甚至说,软件开发人员也“为国王服务”。 每个人都受更大公司的支配,在食物链中更高。 与拥有数百万用户的科技巨头相比,我们只是小小的,无能为力的斑点:数字农民。 感觉特别好多了: 有人在听我说话。 我算,我重要! 即使只是卖给我一个父亲低碳水化合物饮食。 不是说我想让Facebook听我说话,而是令我们沮丧的是,我们对他们的尝试甚至还不够重要。

翻译自: https://onezero.medium.com/why-we-think-our-phones-are-secretly-listening-to-us-4fd4176a43e3

美团饿了么偷听门

相关文章:

这篇关于美团饿了么偷听门_为什么我们认为我们的电话正在偷听我们的声音的文章就介绍到这儿,希望我们推荐的文章对编程师们有所帮助!